Octavio Paz: The house of presence. The experience and thinking of poetics

All societies have cultivated this or that form of poetry, from magical incantations to erotic songs, from prayers to funeral hymns, from songs that rhythmize the work of the laborers to ballads and narrative poems. Songs in the square and in the temple, in the furrow and in the workshop, in the battle and in the feast, in the harem and in the monk’s cell. Not all peoples have novels, philosophical treatises, dramas or comedies; all have poems. […]

Poetry is the memory of peoples and one of its functions, perhaps the primary one, is precisely the transfiguration of the past into living presence. Poetry exorcises the past; in this way it makes the present habitable. All times, from the mythical time as long as a millennium to the sparkle of the instant, touched by poetry, become present. What happens in a poem, be it the fall of Troy or the embrace of lovers, is always happening. The present of poetry is a transfiguration: time incarnates in a presence. The poem is the house of presence.

Mexico, April 12, 1990

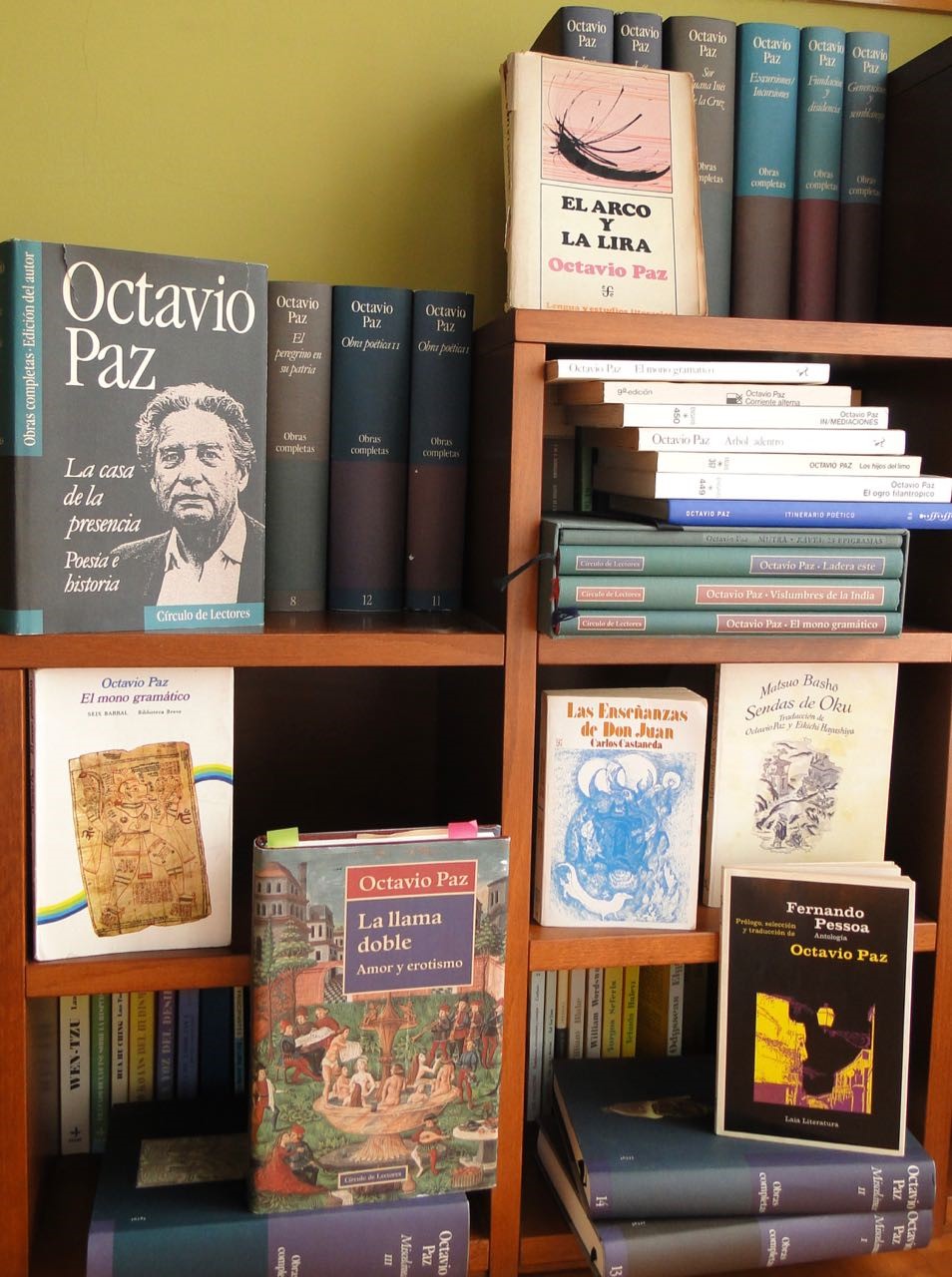

- Octavio Paz, La casa de la presencia (Obras completas, vol. I), Círculo de Lectores, Barcelona, 1991, p. 16 i 27. (Fragment of the prologue to the first volume)

Octavio Paz (1914-1998), internationally recognized as a writer and poet -Nobel Prize for Literature (1990)- also has an extensive essayistic work, not so well known. In fact, of the fifteen volumes of the complete works (1991-2002) only two are of literary creation, the rest, essays: poetic, literary, cultural, anthropological, political, aesthetic, social, ideological, philosophical …, essays that in Paz never cease to have a poetic temper.

Thinking about poetry, poetic thought, but, fundamentally the experience that reveals to us the thinking of poetics, of poiesis; living and life-giving word: house of presence.

As an introduction to kosmos Paz, in summer we read a singular, strange, suggestive, provocative … prose poem written in Cambridge (1970), after his stay in India as ambassador:

The path of poetic writing resolves itself into the abolition of writing: in the end it confronts us with an unspeakable reality. The reality that poetry reveals and that appears behind language is literally unbearable and maddening. At the same time, without the vision of that reality neither man is man nor language is language. Poetry feeds us and annihilates us, gives us the word and condemns us to silence.

- Octavio Paz, El mono gramático, Seix Barral, Barcelona, 1974, p. 113.

We complement this initiation with three reference prologues (1954, 1961 and 1973) that cover a whole geographical arc from Japan through Europe to Central America:

- Matsuo Bashō, Sendas de Oku, translation by Octavio Paz and Eikichi Hayasshiya, Seix Barral, Barcelona, 1981, 33-51

- Fernando Pessoa, Antología, by Octavio Paz, Laia, Barcelona, 1985, p. 5-29.

- Carlos Castaneda, Las enseñanzas de Don Juan, F.C.E., México, 1974, p. 9-23.

We dedicate the first two quarters of the course to one of Paz’s most important texts where he asks what is poetry, what does poetic creation mean: poetry, poem, language, rhythm, verse, prose, image, revelation, inspiration, poetry and history…

Inspiration is that strange voice that takes man out of himself to be all that he is, all that he desires: another body, another being. Beyond, outside of me, in the green and gold thicket, among the trembling branches, sings the unknown. It calls to me. But the unknown is the endearing and that is why we do know, with a knowledge of memory, where the poetic voice comes from and where it goes. I have already been here. The native rock still keeps the traces of my footsteps. The sea knows me. That star one day burned in my right hand. I know your eyes…

- Octavio Paz, El arco y la lira. El poema. La revelación poética. Poesía e historia [1956], F.C.E., México, 1967, p. 180, revised and definitive edition, reedited until today.

In the third quarter, already in the middle of spring, we enjoy a vital and enthusiastic book written at the end of his life. If in the previous one Paz delves into the body of language and poetry, in this last text, written in one go, he narrates the language and poetry of the body:

Poetry and eroticism are born of the senses but do not end in them. As they unfold, they invent imaginary configurations: poems and ceremonies. […] Eroticism is invention; sex is always the same. […]

The original and primordial fire, sexuality, raises the red flame of eroticism and this, in turn, sustains and raises another flame, blue and tremulous: that of love. Eroticism and love: the double flame of life.

- Octavio Paz, La llama doble. Amor y erotismo, Circulo de Lectores/Galaxia Gutemberg, Barcelona, 1993, p. 14, 16 and 9; second edition in Seix Barral, Barcelona, 2001.

Here you will find the program of the seminar, in which we put the texts, object of our studium, in dialogue with several authors that Paz dealt with or are in tune with: Heidegger, Panikkar, Maria Zambrano, Julio Cortázar, Josep Carner, Joan Vinyoli, Robert Graves, George Steiner, Ramon Xirau, Norman O. Brown, José Angel Valente, Hugo Mújica and Pere Gimferrer.

Octavio Paz and Raimon Panikkar met in 1964 in India, and have been friends ever since. In the Panikkar Fund of the Library of the old town of Girona, there are several books by Paz dedicated to Panikkar.

Eduard Muntaner, member of the seminar, made one of the Lecturas Fondo Panikkar (UdG) about this relationship, which you can see here.

The reception of Paz’s work in our country has been very regular, especially thanks to his relationship with what he called “the beloved Barcelona circle”: Carlos Barral, Gil de Biedma, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Goytisolo, García Márquez, Gabriel Ferrater, Pere Gimferrer… Paz often published, in first editions, his books in Seix Barral, and it was Hans Meinke, director of Círculo de Lectores, who encouraged the author’s edition of his complete works.

On the occasion of the centenary of his birth, these interesting articles are published:

- «El poeta que va erotitzar les paraules», La Vanguardia (March 24, 2014)

- «Octavio Paz i Catalunya», Cultura/s. La Vanguardia (July 2, 2014)

- «Barcelona, ciutat talismà del poeta», La Vanguardia (October 2, 2014)